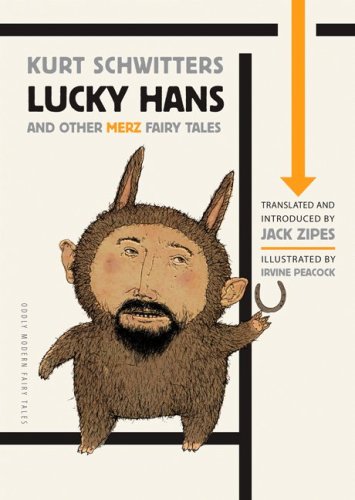

This week I've been reading a wonderful new collection of "Merz Fairy Tales" by Kurt Schwitters. I found the book last weekend on the Recommendations shelf at Unnameable Books, which just relocated inside Brooklyn from Park Slope to Vanderbilt Avenue in Prospect Heights. (It's just down the street from the bar where I went to drown my sorrows after I left a notebook in a cab outside the Brooklyn Museum of Art. The best features of the new bookstore location are totally phenomenological, affecting the body and how it moves. For instance, in the small anthro-soc section in a corridor near the back, the shelf walls are so close together you have to walk backwards out of the alcove just to turn around. Then, in the backyard, the ground is lined with chunky gravel over some sort of acrylic drainage fabric that together produces this wonderful quicksandy crunch when you walk across, making rough sunken pits instead of foorprints.)

The Schwitters tales are pretty fantastic; I'm always a sucker for a sidewise-tragic renovated fairy tale, as in Henry Miller's "Smile at the Foot of the Ladder" or Pierre Louys or for that matter Jacques Demy's "Donkey Skin" and I am all the more excited now to discover that the Schwitters will be the first in a whole series of modern tales, from writers such as Apollinaire, Italo Svevo and Anatole France.

The Schwitters tales are wonderful in their inversion of fable logic, offering instead of morals a sense of the deep arbitrariness by which greed is sometimes rewarded, kindness and hostility both arrive often without pattern or context, and the worst way to make something happen is to try to, or worse, to try to try to. The tale that left the strongest impression on me is actually the first story in the book, in which a solitary swineherd, "serene and also content, but not happy" meets a writer who, to better offer the swineherd a chance at happiness, writes the peasant flesh and blood into his "masterwork" in order to cure his loneliness with the company of fictional characters. A sly remodeling of the wish-granting god or genii, the storyteller offers his own imagination as a basis for wish-granting yet, in pursuit of desire fulfilled the peasant only loses his serenity and contentment, romancing imaginary peasant maidens and contriving a secret identity as a son of an imaginary king. Then, worse, the swineherder bumps up against the limits of the writer's conventional imagination; even in the world of make believe, swineherd princelings should not dare to dream to marry mere peasants, lest they upset the very order of things. Ultimately the swineherd returns chastened to an imaginary reality where happiness is not so important, is only a sort of elusive construct, an absence that exists in the mind of a blithe twittering urbane bourgeois "illustrious writer", scribbling away at the masterwork that is capital, is hierarchy, a pack of diamonds symbolized greater than and less than (<>), a null set fairy tale, a tower of Babel.

In my writing I spend a fairly inordinate amount of time thinking along these lines about happiness and its varieties and its costs, personal and social. Perhaps happiness is not thinking about the future but if that is the case then the series of moments it allows string together only ex post facto meanings. Marjorie Perloff brilliants parses the broken mirror trail of hap-happening-happenstance-haphazard here as a way into Lyn Hejinian's great poem "Happily"; another Marjorie, Marjorie Welish, advising me about poetry a few years ago, told me to focus on events and how they happen. Read the times, she said a few weeks later. As in, I thought, How Happenings Happen, and For Real.

I was thinking about all this, funnily enough, as I watched the new Harry Potter film last week, the latest in this slow-motion maxillofacial maturation series in which, entering early adulthood, some of the child actors' mouths billow sidewise into rakish comedian snaggles while others upturn like jaunty hats, or stretch like nervous rubber bands, taut and slithery. (I've just shaven a three month beard back to choppish sideburns in the last few weeks so I am experiencing my own rediscovery of the over exposed upper lip. Mine is always more marginal than I ever remember though nonetheless very distracting!)

Weirdly, given that I have no serious stake in the Harry Potter, this is the second post on my blog I am offering on the subject of a Harry Potter film. To be honest, each time I've seen one of these movies I mostly ignore the storyline and revel in the guiltily idealized boarding school ambience. The quality that I like best in the Potter films (and which this latest one evokes most of them all because the heart of the film is crushing adolescent angst instead of hero's quest and magical portent and general ology-ology) is of a precious momentousness of Happening that is both extremely slow and totally ephemeral. This is exactly the feeling of existing inside a big, almost but not quite benign institution: there are always very important things happening all over the place all the time but, no matter how many of these important moments you observe or take part in, there are other maybe more important moments that you are constantly failing to attend. You are following one schedule but you so easily could be following another -- and look, right on this calendar, here it is, here is what you missed, here is why there will be such terrible and wonderful consequences.

This was the also the quality I felt watching the naiads-meet-quantum geometry choreography of the Merce Cunningham company that I saw perform last week in Battery Park City, only days after his death. (Just this moment, finding this picture in the Times review of the performance, I discovered that a schoolmate of mine in high school -- which was not so much like Hogwarts, really -- is now apparently part of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company.)

Cunningham's aleatory zen games of dice-rolling ensure that what you see is always a partial performance out of all possible performance permutations, and even in that partial performance one only witnesses a fraction of what is possible. I remember when I saw a performance a few years ago in which he'd collaborated with Radiohead and Sigur Rós at BAM; because of the dice throws determining the order of dances and musical tracks you could never witness the whole or "official" piece, only what happened to occur when a certain part of the music coincided with a certain element of the dancing. Taking this even farther to brilliant effect in the outdoor park setting last week, the dancers flitted between two makeshift stages to perform in which no matter where one stood, one could never see more than one of the two stages; one could enjoy the maths of dancers performing alone and in groups on oe stage but never forget that, just beyond one's peripheral vision, another stage was featuring an altogether different choreography at any given moment, a profusion of beautiful activity and forms.

You might choose one and then other at any given moment but always the choreography would include you, turning your head from side to side, not seeing it all, only a part. My friend Steven had told me earlier in the day, that this literally would be the last ever performance of the Merce Cunningham group since Cunningham had decreed that the group vanish with him. Judging from their nonchalant post-performance exit, I understood that the company would continue performing at least through a final months-long world tour. If I'd known I'm not sure I would have made the effort to hustle us downtown from Farrah's poetry reading earlier in the evening. I'm so glad I saw it though, and its non-continuance continuance seems even more appropriate: one last statement about lastness and the impossibility of one more, followed by one more.

I'm always a little baffled by the ritual of encores that always provide the coda to concerts; the audience knows on some level that, since the lights have not come up to reveal the ugliness of a utilitarian space that has been used utilitarianly, the concert is not over; the performer leaves the stage knowing they will come back; the encore is usually programmed in advance; the audience roars upon the performer's return knowing of course that this would happen and happen almost certainly regardless of their roaring; nevertheless the audience is thrilled that they have participated in making it happen; this thing that dooms the show to be almost over, though it is not over already. When the lights come on without an encore, though, despite it feels often to me in spite of this awareness s if something cheap has been foisted over, I have not been satisfied and who knows if I ever would have been satisfied but I am even less satisfied than I would have been in my otherwise state of dissatisfaction, without the encore, without more. Tomorrow night Farrah and I are going to see Alela Diane, one of her favorite, perform at a bar in Park Slope. Wonder if there will be encores.

Encore: In high school French I had trouble far too long with the word "encore" which for some reason lodged in my head in some mid-ground between 'more,' 'again,' and 'also.'

Encore: I was thinking during the Merce Cunningham show about what if one tried to live one's decision in life according to the Cage-Cunningham aleatory techniques, a roll of the et cetera dice. Then I realized, that's already how it is.

Encore encore: walking back home from the Merce Cunningham performance across the Brooklyn Bridge, I asked Farrah what she thought of the name "Merce." We play this game a lot, plumbing the Baby Name Wizard and thinking of unlikely names. (From our family trees, we often ponder our grandfathers, "Otis" and "Harmon." Harmon, mine, went by a nickname: Berl. Farrah mashes them up: "Otis Berl." "OB." "Obie.") I pondered the possibilities in Cunningham's case - Mercy? eMerson? - but Merce is apparently short for Mercier. I like the mixture of the tender-hearted and the magniloquent-transcendental in the pairing of mercy and Emersonian though. Merce also seems an American variant of Kurt Schwitters' school-of-one movement trademark, Merz. The Fairy Tales book I bought insists on the cover that these are "Merz Fairy Tales" (merz is highlighted in orange amid the other black font words); the introduction describes Merz as a sort of lower-register dada replacement after Schwitters' application rejection from Official Dada (snicker, shudder) on account of insufficient polemical sneering and an excess of jackets and ties. It appears Schwitters dreamed up the term Merz as a sonic glyph signifying this new logic, his call to reject perfectionism in favor of the attainable. Merz was a badge of alienated charm: "a smile at the grave and seriousness on cheerful occasions." Merz is also a parody of capital and art markets and merz-ish merchandising. According to the introduction, the inspiration for the word "merz" comes from the official Kommerzbank in Weimar Germany, the merz extracted so that it echoes with a smidgen of the German word 'ausmerzen,' to demolish, to annihilate. If Schwitters is for creative destruction, though, it is a soft apocalypse that pokes gently into the ribs, an apocalypse only of a wrong way of frowning. In the very engrossing introduction to the Merz Fairy Tales, the series editor Jack Zipes quotes at length a famous Schwitters poem from 1919 that I hadn't read before. I am awfully moved by the ironclad logic of these following lines:

Anna Bloom, red Anna Bloom, what are the people saying?

Prize question:

1) Anne Bloom has a screw loose.

2) Anna Bloom is red.

3) What color is the screw.

Blue is the color of your blonde hair.

Red is the color of your green screw.

That seems like the paradigmatic Merz syllogism: saying "I know, I know,": first ruefully, then sheepishly, then wolfishly. (Both Kurt and Schwitters are such toothy, lupine words in my mouth--total wolf, though maybe a dancing wolf.) In exile in England during the Nazi period in Germany, Schwitters wrote some of his last fairy tales in English. In one, he describes a painter painting a hyperreal three-dimensional portrait not on canvas but on the air itself. The painted figure hovers then blows away in the breeze as a onslaught of verbs: "He trembled and scrambled in the air, and he shivered and schwittered, like the air under him schwittered and shivered... Suddenly he grew quite thick round the middle, blew himself up, burst, and fell into pieces." According to the winking conclusion of this faux-bitter tale, the magical painter gives up his magical craft in the face of all this blowsy schwittering and "therefore, painters now paint plain, flat figures with flat brushes on canvas."

I snuck into a second movie after watching Harry Potter and watched the previews. It turns out there will be another film in the 'can't escape death' gotcha! series "Final Destination" which, instead of dutiful receiving a Roman numeral, will instead be the last last last, ie "THE Final Destination." I'm sure it will not be as beautiful as the claymation extravaganza "Coraline" of last winter but like it, it will be shown in 3-D using the new polarized lens technology that has been named, invitingly, RealD.